Place

History of Sen̓áḵw Village

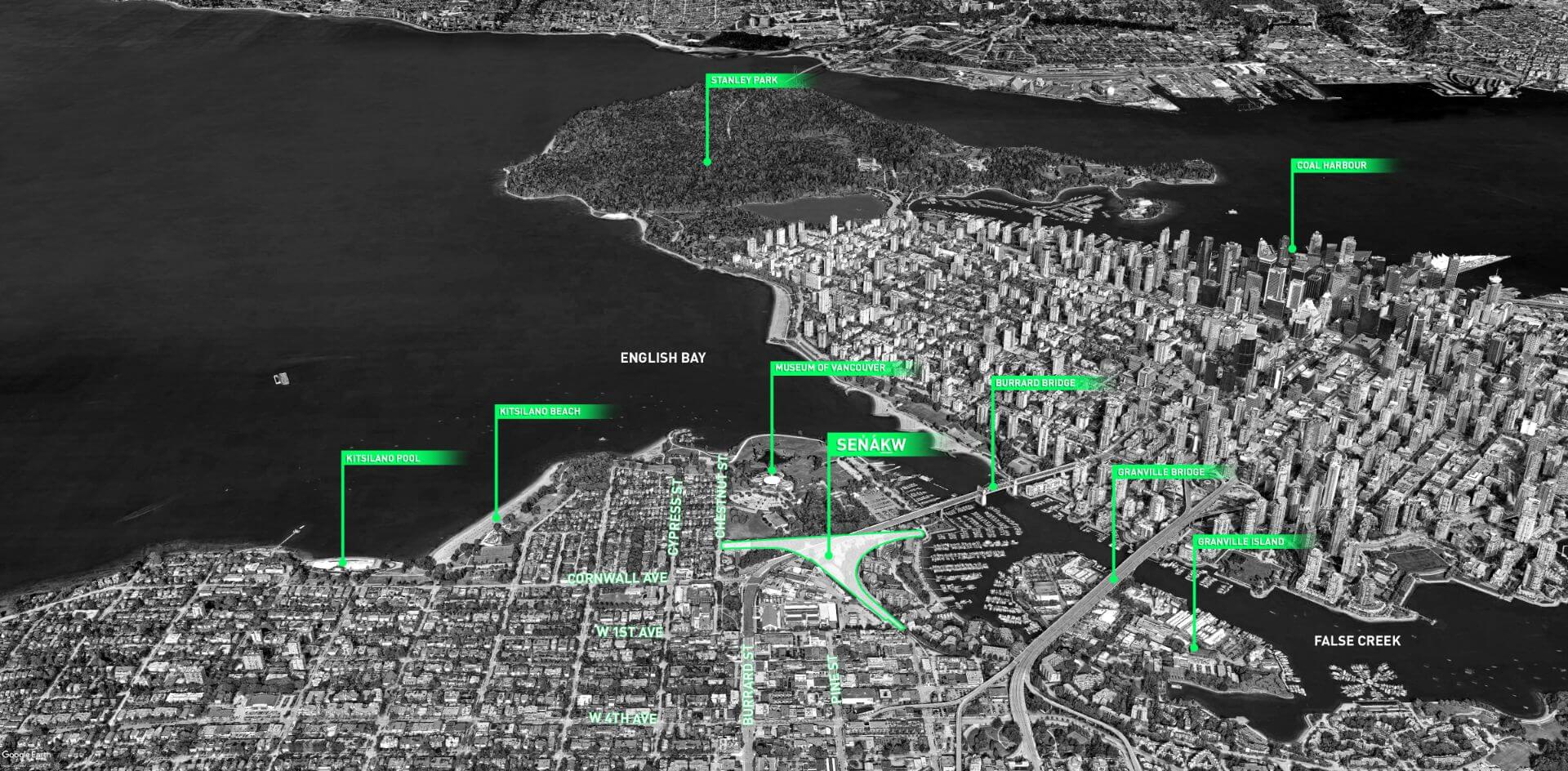

Long before the arrival of European settlers in the Vancouver area in 1791, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) ancestors had a village at Sen̓áḵw. Every year, families from upper Sḵwx̱wú7mesh villages would travel down to Sen̓áḵw, where the lands and waters were ideal for fishing, hunting, and harvesting traditional resources. There was an abundance of elk, beaver, deer, salmon, duck, cedar, and more. The Sḵwx̱wú7mesh People built longhouses and brought neighbouring tribes together for potlatches. Sen̓áḵw was an important hub for trade, commerce, social relationships, and cultural practices.

As the area around Sen̓áḵw began to develop, portions of the reserve lands were expropriated, including over 3.5 acres for railways in 1886, and another 7 acres for railways in 1901. There was a great deal of industrial expansion in False Creek in the years that followed, with mounting pressure for the residents of Sen̓áḵw to vacate their land.

Then, in 1913, the Government of British Columbia forced the illegal surrender of the lands. Families at Sen̓áḵw, along with some of their personal belongings, were loaded on a barge and set adrift. All residents were removed from their land and homes, with nobody permitted to remain at Sen̓áḵw.

The Sḵwx̱wú7mesh People recognized many years ago that sacrifice and investment would be required to pursue a claim to Sen̓áḵw through the courts, and provided the Council of the day with the mandate to do the work necessary to have Sen̓áḵw returned to the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish Nation).

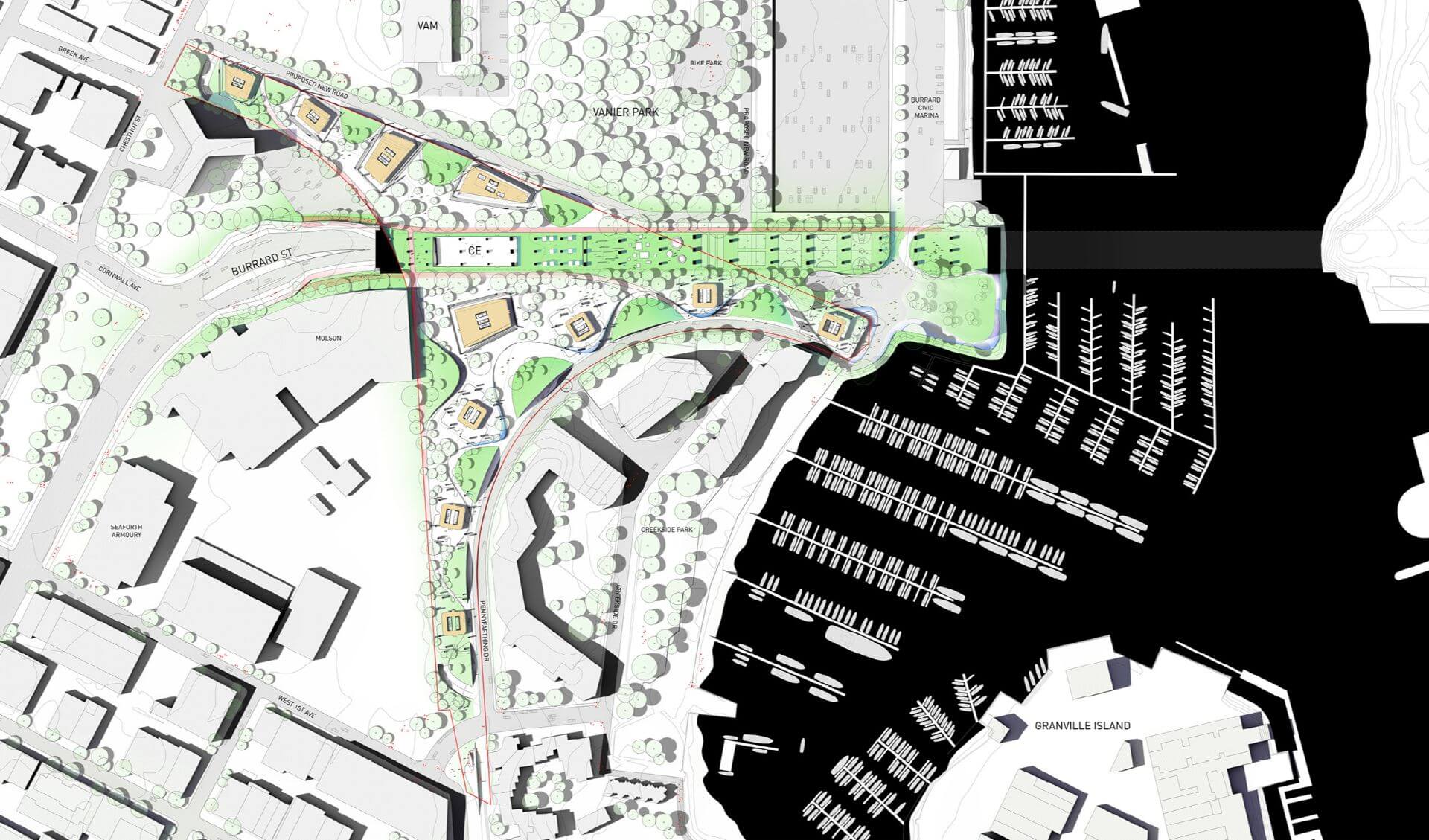

Work started in the late 1960s and continued through the 1970s to prepare to launch a court case to pursue the reclamation of Kitsilano Indian Reserve No. 6. In 1977, Chiefs and Council launched the Omnibus Trust Action against the Government of Canada. Over many years, the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh People, Council, and leaders — including the late Chief Joe Mathias and the late Andy Paull — dedicated their lives to reaching a settlement to these claims. Following decades in the courts — which also heard counter claims by the Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations to interests in the reserve — in 2003, the Federal Court of Canada finally returned 10.48 acres of the original 80 acres to the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw as reserve land.

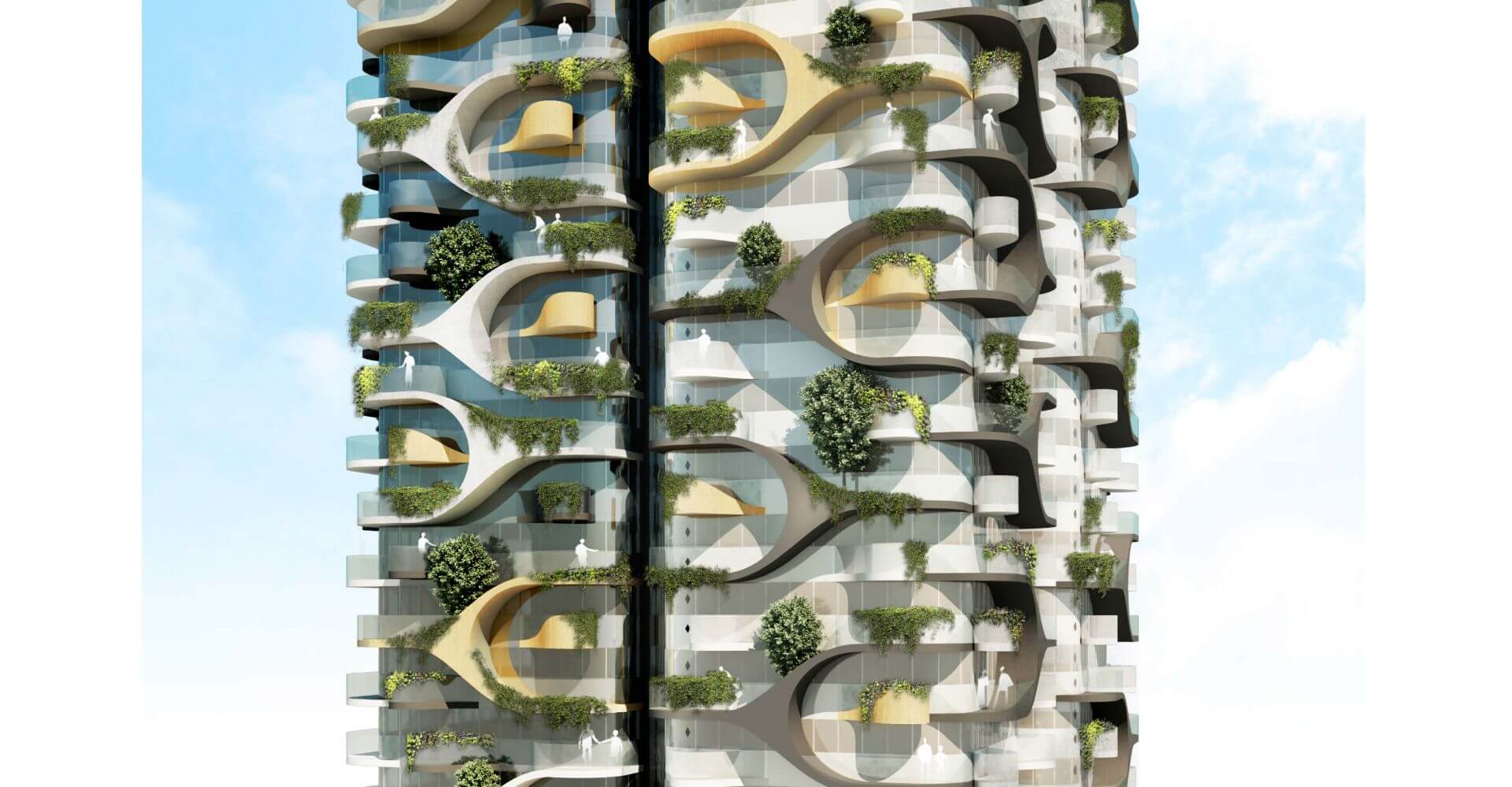

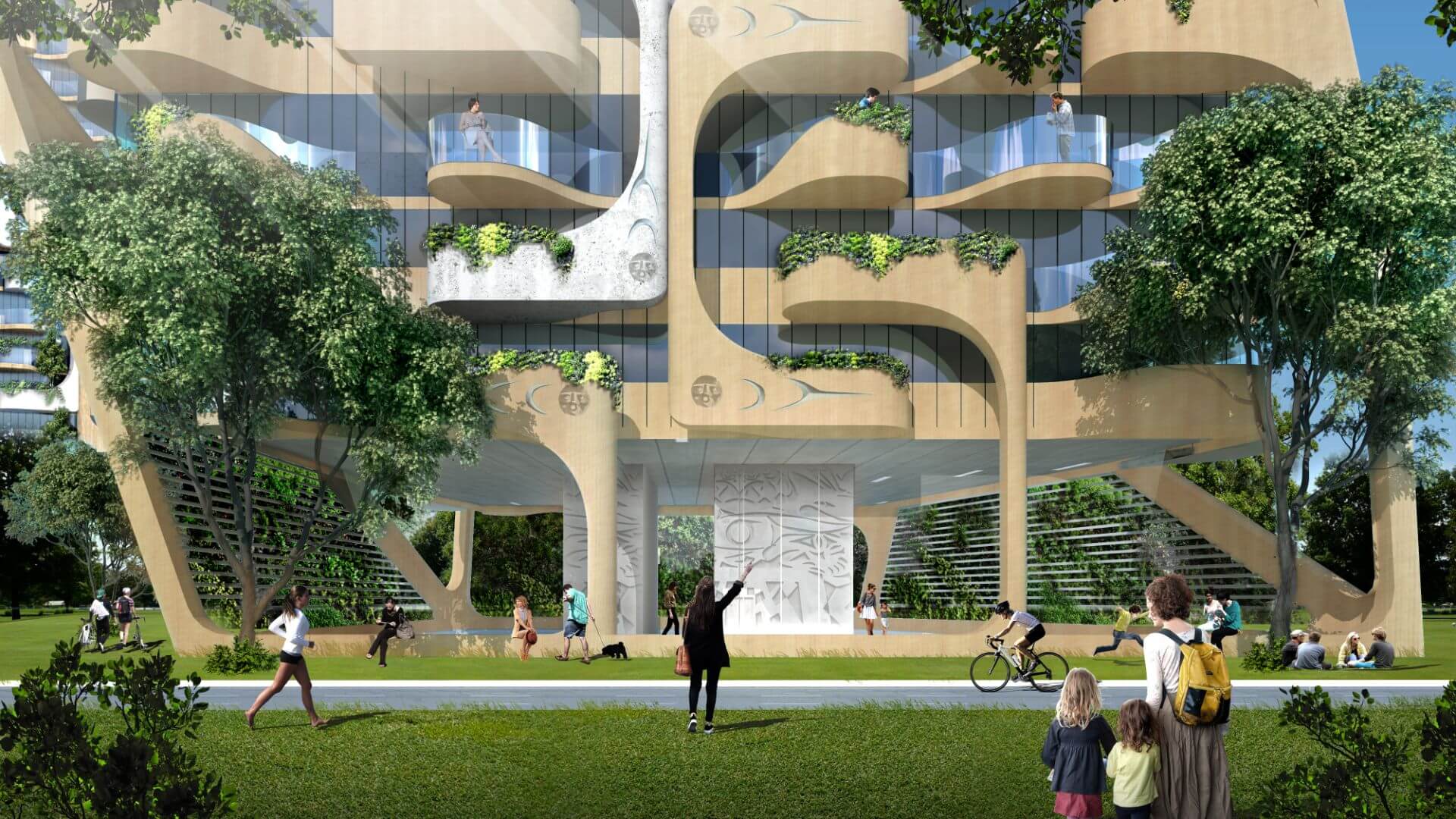

In 2019, the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh People voted overwhelmingly in support of developing Sen̓áḵw in partnership with OPTrust. A few short years later, in 2022, we broke ground, demonstrating Sḵwx̱wú7mesh leadership on climate, urban development, and economic development.